According to research from the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), tire erosion, plastic waste, and industrial granules are the major sources of microplastic pollution. The study found that roughly 80% of these pollutants settle in the soil, with the rest making their way into our air and water. Let’s get into it.

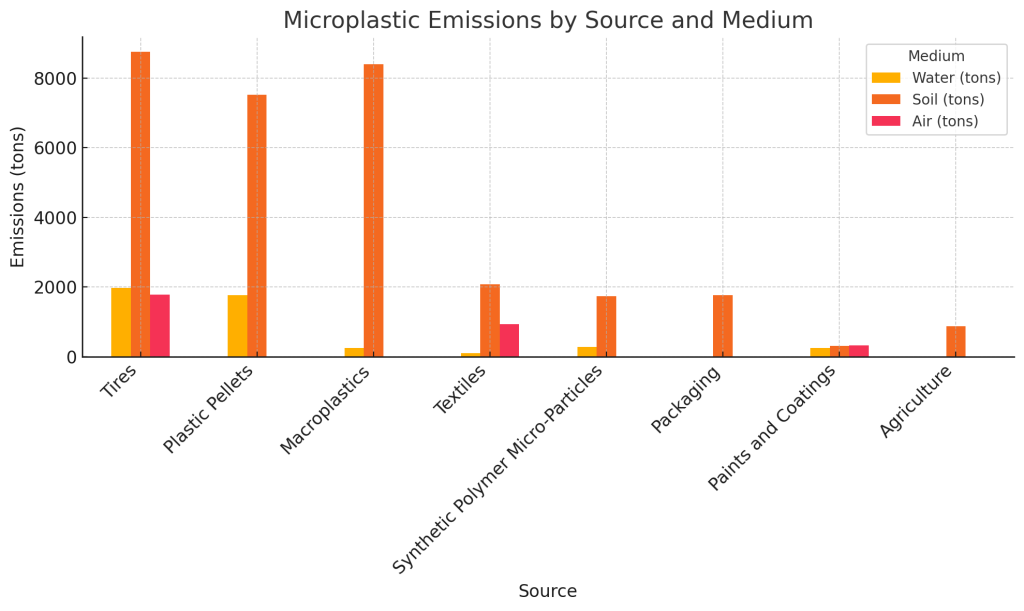

This chart presents a detailed breakdown of microplastic emissions across three mediums—water, soil, and air—originating from different sources like tires, plastic pellets, and textiles.

1. Tires: The Dominant Polluter

Tires stand out as a substantial source of microplastics, contributing significantly across all three mediums. The emissions are particularly high in soil, where nearly 8,750 tons of microplastics from tires accumulate annually. This might not be surprising if we consider the daily wear and tear on tires. Every time a vehicle moves, tire particles are shed, and because these particles are plastic-based, they add up quickly. This continual degradation is a persistent problem that affects both urban and rural areas. Moreover, tires are a key contributor to airborne microplastics as well, with nearly 1,788 tons released into the atmosphere.

In terms of water pollution, tire particles still make a considerable impact, depositing close to 1,973 tons annually. Given the vast number of vehicles in operation, this is a worrying statistic. These particles are often carried by rainwater runoff into rivers, lakes, and oceans, further spreading contamination.

2. Plastic Pellets: The Invisible Contaminant

Plastic pellets, often used as raw materials in manufacturing, contribute almost as much as tires in terms of total pollution—especially to soil and water. With 7,522 tons accumulating in soil and 1,776 tons in water, plastic pellets are silent polluters. What makes pellets particularly problematic is their tendency to escape during transportation and handling, leading to unintentional spillage. These small particles are then dispersed through various means, often unnoticed until they reach environments like soil or water bodies, where they remain for long periods due to their resilience against degradation.

Interestingly, plastic pellets have little to no impact on air quality, according to this data. This might be due to their typically heavier weight compared to airborne particles, which prevents them from easily becoming airborne. However, once in the soil or water, they are incredibly difficult to remove.

3. Macroplastics: A Soil Concern

Macroplastics—think larger plastic debris like bags, bottles, and packaging—account for a considerable portion of soil contamination, with around 8,395 tons deposited annually. This makes macroplastics the second-largest contributor to soil microplastic pollution after tires. While macroplastics eventually break down into smaller particles (microplastics), their journey from visible trash to invisible contaminants can take years, during which they pose threats to wildlife and ecosystems.

Unlike the other sources, macroplastics have a relatively minimal direct impact on water and virtually none on air. However, as they break down in the soil, they may eventually contribute indirectly to water pollution as fragments are washed away by rain or irrigation.

4. Textiles: A Surprising Contributor to Air Pollution

Textiles contribute notably to air pollution, with around 941 tons of microplastics released into the air each year. This is likely due to the synthetic fibers released during everyday activities like washing and drying clothes. While textile pollution in soil and water is also significant, the airborne impact suggests that fibers can easily become suspended in the air, carried by wind, and inhaled by humans and animals alike.

Textile microplastics also seep into soil and water, further spreading their impact. With around 2,083 tons in soil and close to 98 tons in water, synthetic fibers from clothing and fabrics are one of those “hidden in plain sight” sources of microplastics that we often overlook.

5. Synthetic Polymer Micro-Particles and Other Sources

Synthetic polymer micro-particles, which include small fragments from paints, coatings, and other industrial sources, contribute notably to both water and soil pollution. Paints and coatings also stand out for their air pollution potential, with approximately 334 tons of particles entering the atmosphere each year. This might be due to construction activities or general wear and tear of painted surfaces exposed to weathering.

Packaging materials are almost exclusively a soil problem, with minimal contribution to water or air pollution. This probably reflects the tendency for discarded packaging to break down in the soil over time.

6. Agriculture’s Role in Soil Contamination

While the data indicates no direct contribution to water or air pollution, agriculture contributes significantly to soil microplastics. This is likely due to the use of plastic mulches, agricultural films, and other plastic-based products that gradually degrade into the soil. The estimated 880 tons from agriculture reflect the enduring challenge of plastic usage in farming, which can lead to long-term soil contamination.

Overall Implications

The data clearly highlights soil as the primary recipient of microplastic pollution, with water and air following at a distance. This points to a pervasive problem: microplastics are not just a water pollution issue, as often depicted, but a comprehensive environmental challenge impacting multiple ecosystems. Soil contamination in particular is a major concern, as it directly affects agricultural productivity, wildlife health, and can indirectly lead to water pollution through runoff.

This analysis underlines the need for diverse approaches to combat microplastic pollution, such as improving tire technology to reduce wear, enhancing handling protocols for plastic pellets, and rethinking our use of synthetic textiles. Addressing these sources at their origins—whether on the road, in factories, or at home—could significantly reduce the influx of microplastics into the environment.